The Dystopia Files

2010-2012

The Dystopia Files feat. Frédéric D. Oberland at Cinéma des Cinéastes, Paris, 2010

The Dystopia Files is an archive of video clips depicting public interactions between police and protesters in North America since 1999. Typically shot on city streets during protest actions of various kinds, this footage portrays scenes of ritualized conflict that are by turns familiar and shocking. I shot some of the material myself, and gathered the rest from activists, observers, civil rights lawyers (who obtain video shot by police in the course of legal proceedings), and other artists and media makers. I show edited selections from the archive in installations, performances and single-channel videos. I think of protest, and the policing of protest, as public performance, and I'm interested in the ways in which video mediates these performances and inflects their position in the public sphere.

The Dystopia Files installation at G-MK in Zagreb

G-MK (Galerija Miroslav Kralevich), Zagreb, Croatia

Curated by Zelka Himbele

June 9 - July 9, 2011

The Dystopia Files: Toulouse Edition

The Dystopia Files feat. Frédéric D. Oberland

Video projection with performance, Cinéma des Cinéastes, Paris

Curated by Nicole Brenez and Pascale Cassagnau for Le Bal

October 9, 2010

The Dystopia Files feat. Marcy Mays

Video projection with performance, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio

Organized by Ann Hamilton

January 18, 2011

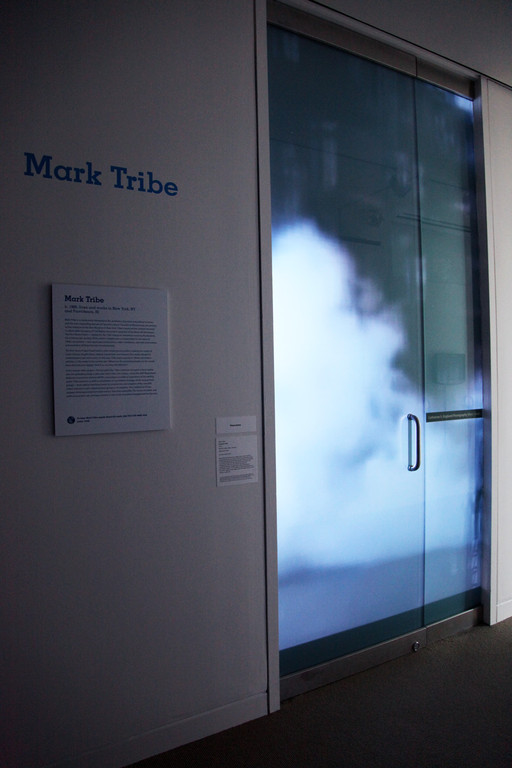

The Dystopia Files installation at the DeCordova Biennial

DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, MA

January 23 - April 11 2010

Exhibitions

The Dystopia Files was exhibited as an interactive installation at the 2010 DeCordova Biennial in Lincoln, MA. Clips from The Dystopia Files archive were rear-projected on a frosted glass door that opened onto a small gallery. The gallery was rigged with a system of sensors and switches that controlled the projection and the lights. When a visitor opened the gallery door (on which the video was projected), the projection stopped and the gallery lights turned on. The gallery was empty except for a set of locked flat files, the drawers of which were labeled with the names of protest groups and political art collectives currently active in North America, ranging from the relatively familiar (Code Pink, The Yes Men) to the obscure (Shadowy Revolutionary Cell, Zombie Flash Mob). The projection remained off, and the lights remained on, as long as the room was occupied.

The installation functioned as an inverted camera obscura, selectively revealing and concealing the contents of the archive. The archival video could only be seen from outside the gallery, where, because of the vertical proportions of the door, large parts of the video frame were obscured. When a viewer attempted to enter the archive, the system of surveillance and control responded by clamping down on the spectacle of conflict. The installation's operations mirrored the interplay of exposure and occlusion that has characterized the visual representation of protest in recent years: each group plays its part, rendering itself visible before the eyes of ubiquitous video cameras. But, because the video captured by each party serves an evidentiary function in legal skirmishes and public relations campaigns, it is carefully guarded, and released only under specific conditions of display. The few clips that find their way into public view, such as the widely circulated video of protesters burning police cars at the 2010 G20 Summit in Toronto, tend to be presented with little context, as transparent signifiers that speak for themselves.

The installation rehearses this decontextualization by displaying what activists sometimes call "protest porn" without any background information, yet its interactivity suggests not only that there is more than meets the eye, but also that state power functions as much through classification (e.g. the naming of suspects) as it does through denial of access (to what it knows).

Background

The 1999 WTO protests in Seattle marked a turning point both for political protest and for the ways in which the state attempts to control it. Protesters developed new models of organizing (e.g. affinity groups and spokescouncils) and new tactics of direct action. Governments, in turn, heightened security measures by denying protest permits, surveilling and infiltrating activist groups, preemptively detaining activists, creating militarized security zones, and deploying "less-lethal" weapons such as tasers, tear gas, and Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRADs). The policing of protest intensified again after 2001, as laws preventing domestic spying were repealed, anti-terrorism funding flowed to law-enforcement agencies, and larger patterns of militarization and control emerged. Activist groups responded to this new environment by adopting "security culture" practices intended to prevent infiltration and avoid surveillance.

Political protest has become a public ritual in which activists and police play socially-defined roles and perform unscripted yet predictable actions for an imagined audience represented by video cameras. The video captured by these cameras reflects the aesthetics and power dynamics of these performances (the storm trooper gear, weaponry, and choreographed movements of the police, as well as the costumes, signage, props, chants, and sometimes creative actions of the protesters) and their mediated representations (camera angles, framing, movement, compression artifacts, etc).

Photos of The Dystopia Files installation at the DeCordova Biennial

Video stills

In the press

The Dystopia Files was named one of the top five films of 2010 by French film critic and curator Nicole Brenez in Sight & Sound, a publication of the British Film Institute. Also on her list were Film socialisme by Jean-Luc Godard, The End of the World Starts With One Lie – First Part by Lech Kowalski, and X+ by Marylène Negro.

ArtScope Magazine: "Among the threads [in the Biennial] is a concern with archival practices that runs through not only [Ward] Shelley's cardboard mountain but also Mark Tribe's ingenious installation 'The Dystopia Files.' Tribe, who teaches at Brown University, has transformed the DeCordova's photography study space into a simulated surveillance archive. From outside the unlit room, viewers witness video footage of conflicts between police and protesters rear-projected onto its closed frosted glass door. Before reading the curator's description, they hesitate to enter. In fact, I saw a man reprimand his daughter for trying. And this hesitation generates an aura of trespass around the work, one heightened by a motion-activated control system inside that unexpectedly stops the footage and turns on the lights.

"The room's interior betrays 44 locked flat files (actually the DeCordova's photo collection), which Tribe has relabeled with the names of political art collectives and activist groups, giving viewers the sense of having infiltrated the secret archive of a hegemonic, Orwellian regime. Perhaps obviously, the installation comments on the revival of COINTELPRO-like federal surveillance practices in the U.S. following 9/11 and the Patriot Act. If you stand still long enough, however, more provocative interpretations emerge: the room darkens and the footage resumes (now mirrored in front projection) as you switch roles from threatened intruder to comfortable insider. Tribe gives you the opportunity to play both surveyor and surveyed, hinting at how the gap between the security culture of the state and its critics closes when the latter adopt what he calls 'a defensive posture that mirrors the logic of the forces they seek to resist.'"

- Mark Drummond Davis, "A Dense Web: The 2010 DeCordova Biennial."

Special thanks to:

Helena Anrather, Glassbead Collective, Larry Hildes, Sarah Kay, Joshua Kopin, Brandon Neubauer, Nikita, Shruti Parekh, Sarah Sharp, Time's Up Video Collective.

Funding for The Dystopia Files was provided by the Experimental Television Center’s Finishing Funds program, which is supported by the Electronic Media and Film Program at the New York State Council on the Arts.